Busy college students don’t spare a glance at the tag on university merchandise. However, the inconspicuous shirt may lead to a trail of greed and abuse.

$39 may not seem like much to some, but it is the price of a regular university logo-stamped shirt. Foreign workers make most university apparel. For example, for many Honduran families, the price of a regular university shirt is over a third of their weekly paycheck. Just $97, the slightly lower end of a livable wage in Honduras, although, it is barely enough to get by for many Honduras families, according to Journal Star.

“The truth is no, it is not enough money to really maintain a home. Our salaries are low. We aren’t able to cover all of our expenses with this salary,” Cadona Bahr said, in an interview with Journal Star, who is a worker in factories’ ironing room.

While universities make millions in profit from merchandise sales, factory workers take home less than 1% of those profits.

Omaha World-Herald researchers have found, not only is university apparel manufacturing responsible for not paying their factory workers but has had their labor rights violated; such as union-busting (actively destroying the power of a trade union or trade unions), forced labor and sexual harassment.

“We continue to see labor rights violations in a lot of university factories,” Scott Nova, Executive Director of the WRC (Worker Rights Consortium), said in an interview with The Omaha World-Herald.

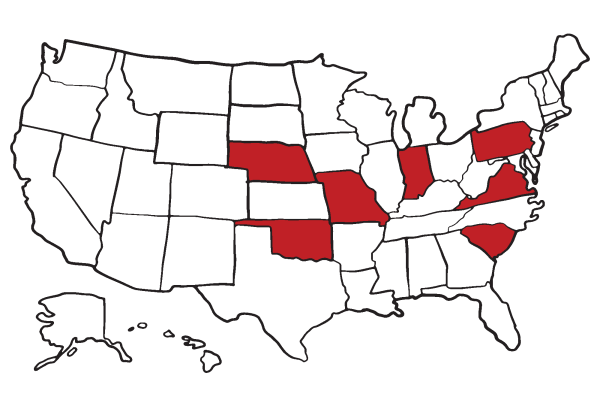

Universities that have violated labor rights include Oklahoma State, University of Missouri, University of Virginia, University of South Carolina, Penn State, Purdue University, University of Nebraska Lincoln and more.

According to Journal Star, this year alone UNL raked in over 4 million dollars in royalties from state apparel. The Nebraska-Lincoln shirt sells for $39.99, while the worker who made that shirt will take home a measly 24 cents.

Many organizations have made strong headway in the fight for fair labor rights in foreign countries, by funding and creating institutions like the WRC and FLA (Fair Labor Association).

These associations have helped create many rules for having mass-produced university apparel, making it harder for universities to underpay their factory workers. These organizations also compose lists of universities that have factories and regularly monitor working conditions.

According to the Journal Star, researchers say that this has made a positive impact on factory conditions, but more needs to be done.

“Consumers have become more aware of the concept of fast fashion, but they tend to think of brands like H&M and Shein first,” Emily Stochl, advocacy manager at Remake (an advocacy group for fashion sustainability), said. “They forget that all of the biggest fashion brands, whether they are a big-box retailer, designer, former mall brands or sportswear are manufactured in similarly exploitative conditions.”

It’s clear that a change needs to be made to end labor rights violations. Unfortunately, the solution isn’t clear. Many think that college students should take a stand against these violations, others think that universities are at fault. Many others think this is another example of big-brand corporations exploiting minimum-wage employees. The end solution may not be clear, but it is every consumer’s responsibility to not feed into corporation greed and abuse.